It seemed as though Brice Marden had always been there and always would be. That was an illusion, of course, but a comforting one. His first show, at the Bykert Gallery in 1966 when he was just 28, is one of those legendary debuts that shook the art world (then defined as about 100 New Yorkers)—like that of Jasper Johns at the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1958, or Frank Stella’s at the same venue two years later. Have gallery shows since then ever seemed to take on such historical importance?

But that was all before my time. For me, the great moment was 1987, with Marden’s first show at what was then called the Mary Boone/Michael Werner Gallery, when we saw that Marden had fearlessly taken his work apart and put it back together, differently. The subtly hued and densely textured monochromatic panels of the previous two decades had shed their skin, as it were, to show their gestural bones and sinews. Like Philip Guston forsaking abstraction for images, but within the realm of abstraction, Marden had chosen renewal over repetition.

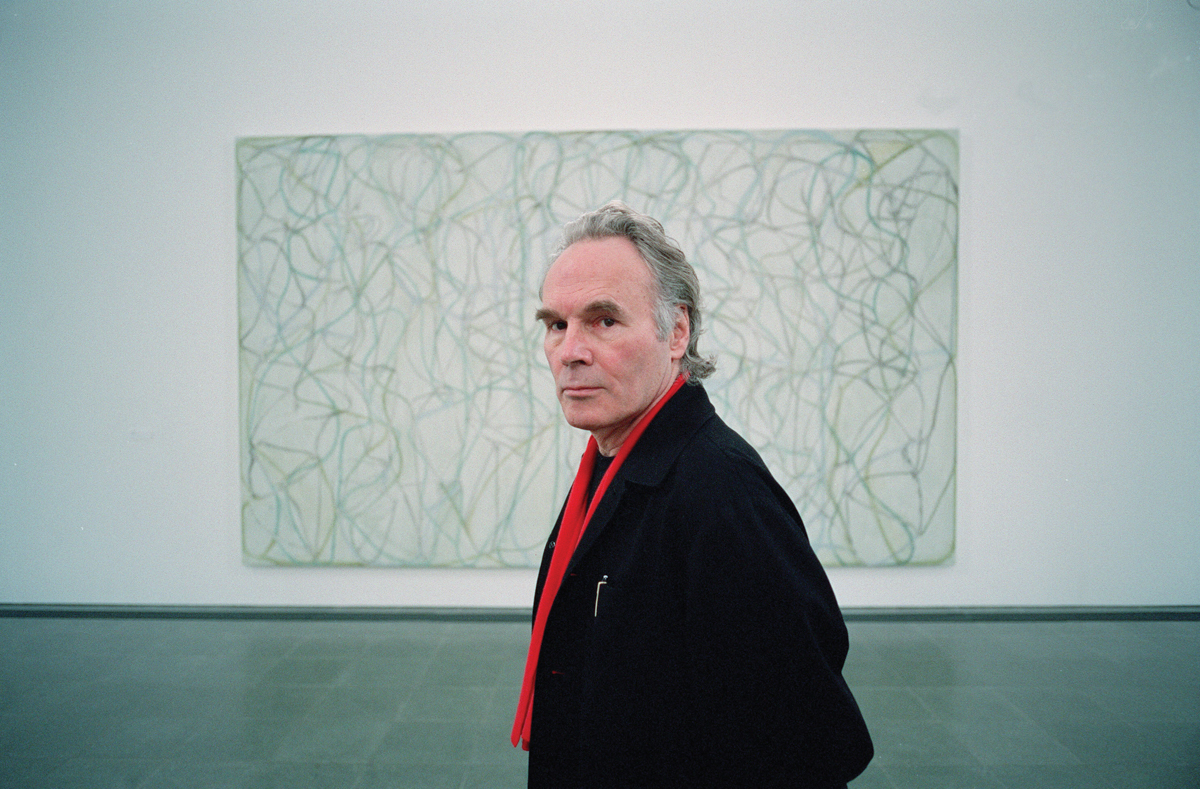

There are a couple of experiences that come to mind when I think of Marden. One took place in 2000, when I was visiting London. A friend had organized a show of Marden’s work at the Serpentine Gallery and invited me for a walkthrough with the artist and some students ahead of the opening.

I don’t remember exactly what Marden said, but I remember vividly his physical comportment as he spoke in front of his paintings, a certain way of pointing toward things that came not from the shoulder or the wrist but from the elbow, with the upper arm down, close to the torso, and the forearm moving freely. I thought back to pictures I’d seen of Marden in his studio and realized that this must be something like the way he used his arm in painting.

That seemed like a notable observation, but hardly a surprising one—the same motor neurons being involved in pointing and painting, probably. The surprise came later, when I attended the exhibition’s opening. As I strolled around trying to get another glimpse of the paintings through the crowd, I noticed that people who’d stopped in front of this or that work to discuss it—people who had not been present at the walkthrough to see Marden as he spoke—were using gestures very similar to the artist’s own. That was the revelation: that this art could induct its viewers not just into the painter’s way of seeing but into his way of physically inhabiting the world. It was the most concrete possible demonstration of what I already knew intellectually: that Marden’s was an art of rare power.

My other Marden anecdote dates a full decade before that. I was in Pittsburgh for the opening of the Carnegie International. Some of us invited visitors were offered a bus tour of the area, including a visit to Fallingwater, the amazing Frank Lloyd Wright house about 70 miles out of town. As we were wandering through the place, I stopped to check out a painting on the wall. The style, probably from the 1950s, was unfamiliar, and there was no signature visible. Who do you think the artist is, I wondered out loud to whomever happened to be nearby. Standing next to me was Marden, who immediately answered with the name of an artist I did not know. I don’t remember what else he said, or even what the name was, but I do remember his reply when I expressed my wonder at the fact that he could instantly recognize such an obscure artist. He brushed it off. “Painters know painters,” he said.

Those two stories sum up two facets of Marden’s art that were rarely so harmoniously integrated as in his work. There’s the immersion in tradition, the urge to know all that had been done in the thousands of years that human beings had been painting; in this sense, Marden was totally inside painting the way an angel is inside paradise (or a devil, as John Milton knew, is inside hell). This is the aspect of Marden’s work that has always made it enjoyable to see his exhibitions in the company of painters, when one can learn from their amazement at what they’re seeing and how it was done that would never occur to a non-practitioner. But then, as my experience in London showed, Marden’s paintings are extraordinarily generous in their way of quietly inviting viewers of all sorts into this inner world of the painter painting. He managed to make each of us a little bit more an artist.

This article appears in the Winter 2023 issue, p. 36.