Brice Marden, an acclaimed painter whose abstractions quietly pushed the style in new directions, repeatedly injecting it with new life during an era when painting was presumed to have hit a wall, has died at age 84.

His daughter, Mirabelle Marden, wrote on Instagram that Marden had died on Wednesday in his home in Tivoli, New York. “He was lucky to live a long life doing what he loved,” she wrote, noting that he had continued painting up until Saturday.

From the 1960s on, Marden painted in many different modes, often taking the oil-on-canvas approach at a time when other painters were untethering the medium from traditional models. Marden’s style may have made him different from many of his colleagues with more explicitly conceptual ambitions, but he continued to find admirers because of it.

The critic Roberta Smith, writing on the occasion of a Museum of Modern Art retrospective in 2006, said that Marden had obtained “a kind of flame-keeper status—something like the Giorgio Morandi of radical abstraction, a maker of inordinately beautiful, exquisitely made (and expensive) artworks.”

Peter Schejldahl, writing on that same exhibition, put it similarly: “Marden may usefully be considered a late-entry Abstract Expressionist: a conservative original, the last valedictorian of the New York School.”

Marden’s first solo show, in 1966 at New York’s Bykert Gallery, featured a grouping of monochromes in muted colors, each with surfaces that had been rendered matte via the use of beeswax. Critics didn’t respond well to them at the time, finding them to be knockoffs of works by other, more famous artists, including Jasper Johns, whose 1964 Jewish Museum show was manned by guards such as Marden himself.

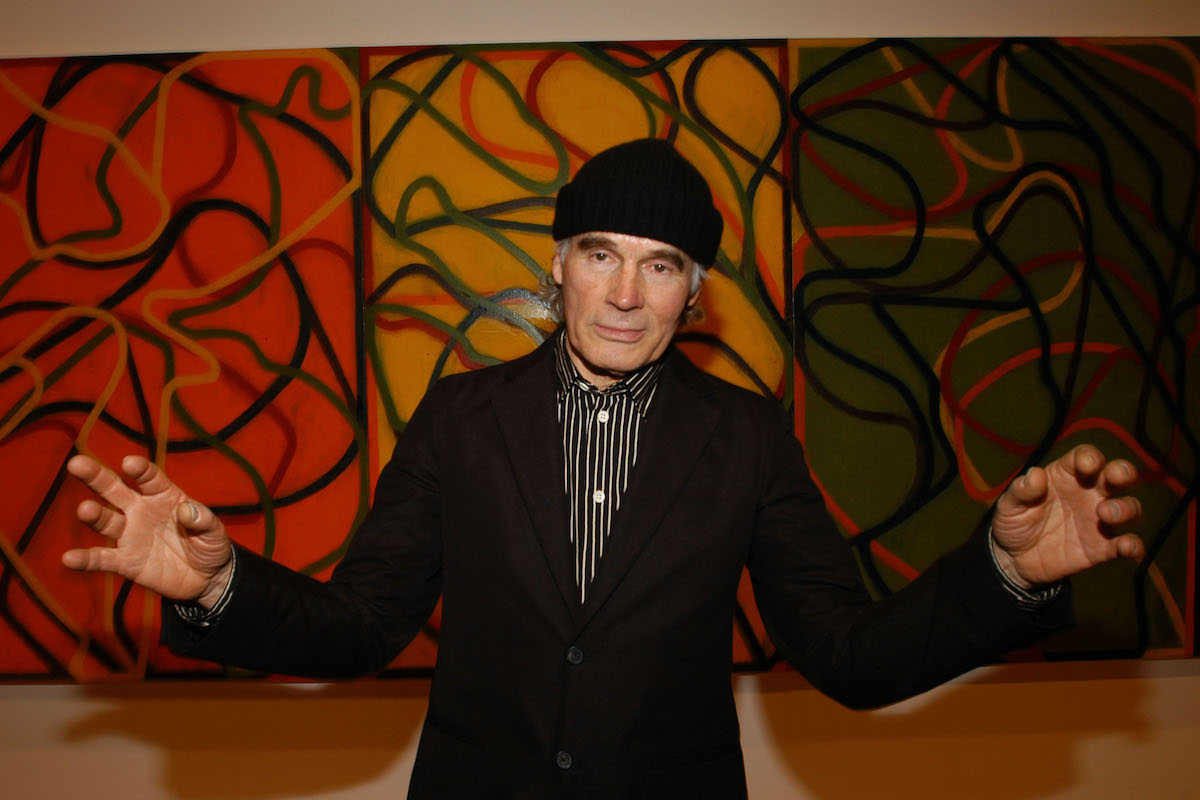

But by the end of his career, Marden’s art had diverged significantly from that formula. He painted abstractions featuring spaghetti-like lines arrayed across vibrantly colored planes and drew minimalist drawings that took their inspiration from Chinese painting. He proved himself a tireless innovator time and again.

Throughout his different bodies of work, Marden remained committed to working in abstraction, a mode that was thought, by the 1960s, to have reached its logical endpoint with Abstract Expressionism more than a decade earlier. “For me, abstraction is the real way of the twentieth century because you’re not leading the viewer too much,” he told painter Chris Ofili in a conversation for Artforum.

By the time of Marden’s first Bykert show, artists like Johns and Robert Rauschenberg had laid down the gauntlet, incorporating everyday objects into their paintings and depriving their art of any notion of artistic genius that accompanied Abstract Expressionism. Marden, rather than shying away from that medium, took up these artists’ challenge. Speaking of Johns and his famed paintings of the American flag, Marden once told the New York Times, “he added another dimension to what is reality in painting. Is a flag real?”

Notably, Marden borrowed from Johns the use of encaustic, a medium that employs wax to give the paint more body. His early work also owed a lot to Rauschenberg, for whom Marden served as an assistant during the mid-’60s. Some of Marden’s monochromes from that period take the form of multiple panels, a choice that owes something to Rauschenberg’s landmark 1951 White Painting.

These early works involved a process that was more unusual than it first appeared. To obtain his smooth surfaces, Marden would apply paint with a little cooking spatula. Although his surfaces would become flat, with few strokes delineated, he made small scratches too, allowing more defined pops of color to peek through. “It’s a very hand-made surface,” Marden said in an interview with MoMA. “And then I would make some decisions about which way to take the color, and then, at another point, redo the whole exercise.”

The emphasis on doing, redoing, and revisiting pervaded Marden’s oeuvre for the rest of his career.

Brice Marden was born October 15, 1938, in Bronxville, New York, not far from Manhattan. His father worked as a mortgage servicer. Marden came to art through his neighbor, a painter; he studied at the Boston University of Fine and Applied Arts and later, as a graduate student, at Yale University, where his cohort included Chuck Close, Robert Mangold, and Richard Serra.

Informally, Marden studied art history as well by visiting museums. In Boston, he favored the paintings of Édouard Manet and Francisco de Zurbarán. When he went to Paris during the mid-’60s for a period, he visited the Louvre often.

The artists of the past whom Marden came to love all worked in a figurative mode, even though Marden explicitly did not. Yet some of his paintings refer to people. One purplish monochrome is titled after Bob Dylan; another from the era bears Nico’s name. What relationship these paintings actually bear to these singers, both of whom Marden knew personally, remains unknowable.

He continued to use titles allusively during the ’70s, when he began making a series of works during a trip to the Greek island Hydra. The “Grove Group” paintings specifically take their inspiration from olive trees he spotted there; they feature large planes of olive and blue. Critic Robert Pincus-Witten, viewing them as relating to Greek mythology, wrote that the paintings were akin to “muses gathered anew at a mouseion.”

During the ’80s, Marden embarked on an array of artworks that took their inspiration from Chinese calligraphy, with tangles of lines that cross again and again.

The beloved “Cold Mountain” series, produced between 1989 and 1991, took its title from Tang Dynasty poet Han Shan, whose name can be translated to Cold Mountain. Marden began the paintings by drawing from a landscape, then taking his sketches into his studio, where he would translate what he saw to canvas. Speaking to the painter Pat Steir, Marden said he was specifically interested in calligraphy’s visual principles as he had done this.

This was a notable departure from his monochromes, and Steir questioned Marden about whether he considered beauty to be an important component of these works. Yes and no, he told her, explaining, “one of the reasons I wanted to do this work was that by using the monochromatic palette in the past, basically all I could get were chords. I wanted to be able to make something more like fugues, more complicated, back-and-forth renderings of feelings.”

Never one to opt for an easy way out, Marden continued to challenge himself well into the later stages of his career. In 2019 he told the New York Times that he had started to paint with white. “White to me has always been a corrective color. You paint things out with white,” he said. “I’m trying to break my own rules.”

In recent years, Marden has ascended to the status of art star. Having appeared in three editions of Documenta, five Whitney Biennials, and one Venice Biennale between the 1970s and ’90s, Marden’s fame was well-cemented by the time his art started selling for millions of dollars at auction in 2000s. Still, some considered it a surprise when, in 2017, he departed his longtime dealer Matthew Marks for the mega-gallery Gagosian, a decision Marden said was prompted by a need for change during the later stages of his career.

“Brice Marden was one of our greatest American artists, whose achievement in continuing and extending the tradition of painting has long been recognized and celebrated the world over,” dealer Larry Gagosian said in a statement. “He was a painter of rare insight into the pleasure and poetry of his medium; always dedicated to gesture, chance, substance—the elemental matters of art. Brice and Helen have been friends of mine for many years, and it has been an honor to share his masterful work with an international audience. This loss is profound, and he will be missed.”

Marden had been battling cancer for the past few years. While he had not often discussed his disease in interviews, his wife, artist Helen Marden, publicly documented his treatments in an attempt, she said, to encourage others to feel more familiar with it.

Even as he faced his cancer diagnosis, Marden did not stop painting. He has had numerous solo shows in the past half-decade, many of them featuring new works. That method of working only made sense for an artist who had toiled restlessly his entire career.

“I’ve shown a painting two times before I thought it was finished,” he said in his 2006 conversation with Ofili. “I’d take it back, rework it, put it out again, then take it back and rework it again.”