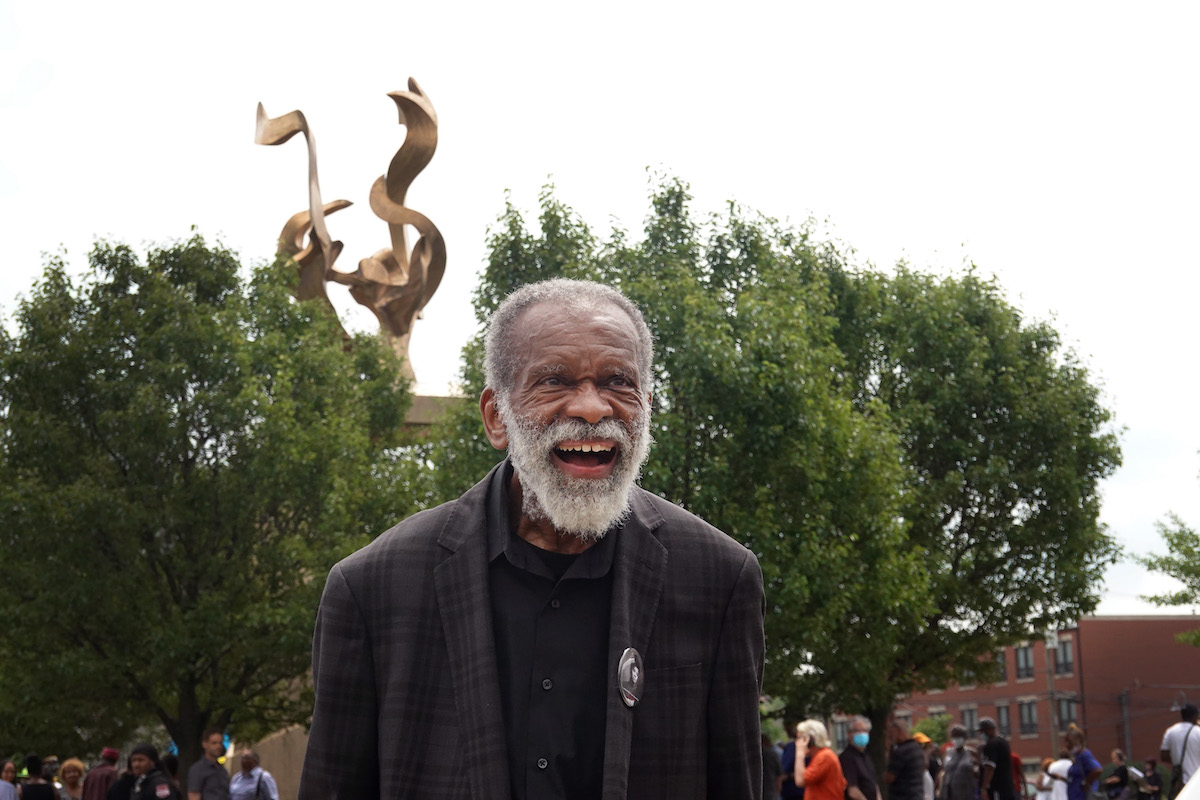

Richard Hunt, a sculptor whose works composed of bent metal and welded steel have been widely seen across the US, both in museums and public sites, has died at 88. According to an obituary posted to the artist’s website, he died in his Chicago home on Saturday. A cause of death was not announced.

Hunt’s sculptures wind their way through space, evoking figures which transmute and grow, their bodies altering in the process. Though they are abstractions, these works also sometimes visualize elements of Black history.

Widely regarded as one of Chicago’s most important artists, Hunt first achieved acclaim during the late ’50s and would go on to find a national following by the start of the ’70s. When New York’s Museum of Modern Art mounted a survey of Hunt’s sculptures, drawings, and prints, New York Times critic Hilton Kramer effusively praised him as an exceptionally gifted artist who had matured early on—a feat, Kramer said, that few others could claim.

He would go on to make an array of monumental sculptures for highly visible public venues, including ones in Harlem and Chicago. In 2022, Hunt was commissioned to do a new work for the Obama Presidential Center in Chicago, which will open in 2025. Titled Book Bird, it will feature a bird perched atop a book, ready to take flight.

Another forthcoming sculpture from Hunt, a 15-foot-tall work titled Hero Ascending, will be installed near the home of Mamie Till and her son Emmett Till, a Black Chicagoan teen who was lynched by a white mob in 1955 after he was accused of flirting with a white woman. Hunt had attended Emmett’s open-casked funeral, and said in his artist statement that he aspired to do him justice. “It is one thing to make art that is a portrait, but for something like the Middle Passage or Emmett Till, you want to develop art that is not a portrait of Emmett Till but something that projects his life, ideas and ideals beyond his lifetime,” Hunt wrote. The sculpture is set to be installed next year.

Richard Hunt was born in Chicago on September 12, 1935, to parents who were descended from enslaved people. His father was a barber; his mother, a librarian. As a teenager, he took classes at the junior school of the Art Institute of Chicago, whose college he would later attend to study art education.

“Sculpture of the Twentieth Century,” an acclaimed 1952 MoMA survey of recent developments in the medium, made its way to Chicago the year after, and Hunt was taken by what he saw. He was particularly drawn to the work of the Spaniard Julio González, whose sculptures translated the biomorphism of modernist abstraction to the third dimension. Hunt once labeled González’s sculptures “drawing in space,” and would come to emulate some of the artist’s innovations himself.

While still in school, Hunt showed his art locally at fairs, earning an audience in the process. After graduating in 1957, he traveled to Europe, then was drafted into the US Army and was forced to return home. Having been stationed in Missouri and Texas, he emerged from his two-year draft in 1960 and moved to New York. But, feeling as though he already he had the art-world connections he needed, he did not remain long.

Amid all his travels, Hunt continued to produce sculptures and prints. In 1958, he made Hero Construction, a sculpture resembling a person whose innards come apart as it grows new limbs. Formed from disused piping and found automobile parts that Hunt welded together, it is owned by the Art Institute of Chicago. “The idea was to suggest a hero, and not to make a hero,” he said in a 2021 interview conducted by curator Jordan Carter.

Other works from the era are composed of unruly copper and steel elements that spider through space, causing them to resemble alien creatures. The welding technique that Hunt used to form them occasionally recalls the work of the Abstract Expressionist David Smith.

Later works would move beyond formalism, into an epic engagement with Black history. Slowly Toward the North (1984), a work owned by the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, is a hulking mass that recalls a plow fused with a train; Hunt intended it as a reference to forms of labor Black Southerners took up as they moved north as a part of the Great Migration. Swing Low (2016), a 1,500-pound bronze creation commissioned for the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., twists across the ceiling from which it is hung and refers to a famed Black spiritual.

Last month, the market juggernaut White Cube added Hunt to its roster. Sukanya Rajaratnam, the gallery’s global director of strategic marketing initiatives, told ARTnews at the time that Hunt was “a giant hiding in plain sight for decades.”

Hunt is survived by his daughter Cecilia and his sister Marian.

He remained hard-working until the very end. In 2022, with multiple big artworks on the horizon, Hunt was asked if he ever took a day off. “Not if I don’t have to,” he said.