Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in On Balance, the ARTnews newsletter about the art market and beyond. Sign up here to receive it every Wednesday.

A little over a year ago, just as the art world was emerging from the pandemic, Marc Payot, co-president of mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth, and dealer Nicola Vassell started having conversations about the challenges of the current gallery ecosystem. Vassell had opened her eponymous New York gallery in 2021, after stints working for Deitch and Pace galleries, and as an independent consultant. As Vassell recalls it, the conversations led to the question of the challenges faced by galleries of different scales. Was there a way. they wondered, that galleries could work together to support a thriving ecosystem, rather than one where artists left galleries like Vassell’s for those like Hauser?

“We all had a lot of time to think during the pandemic,” Payot told ARTnews recently, “and I came to the realization that the art world is in a state where the few very large successful galleries are becoming more and more successful and larger, and for the rest of the ecosystem, things are very tough.”

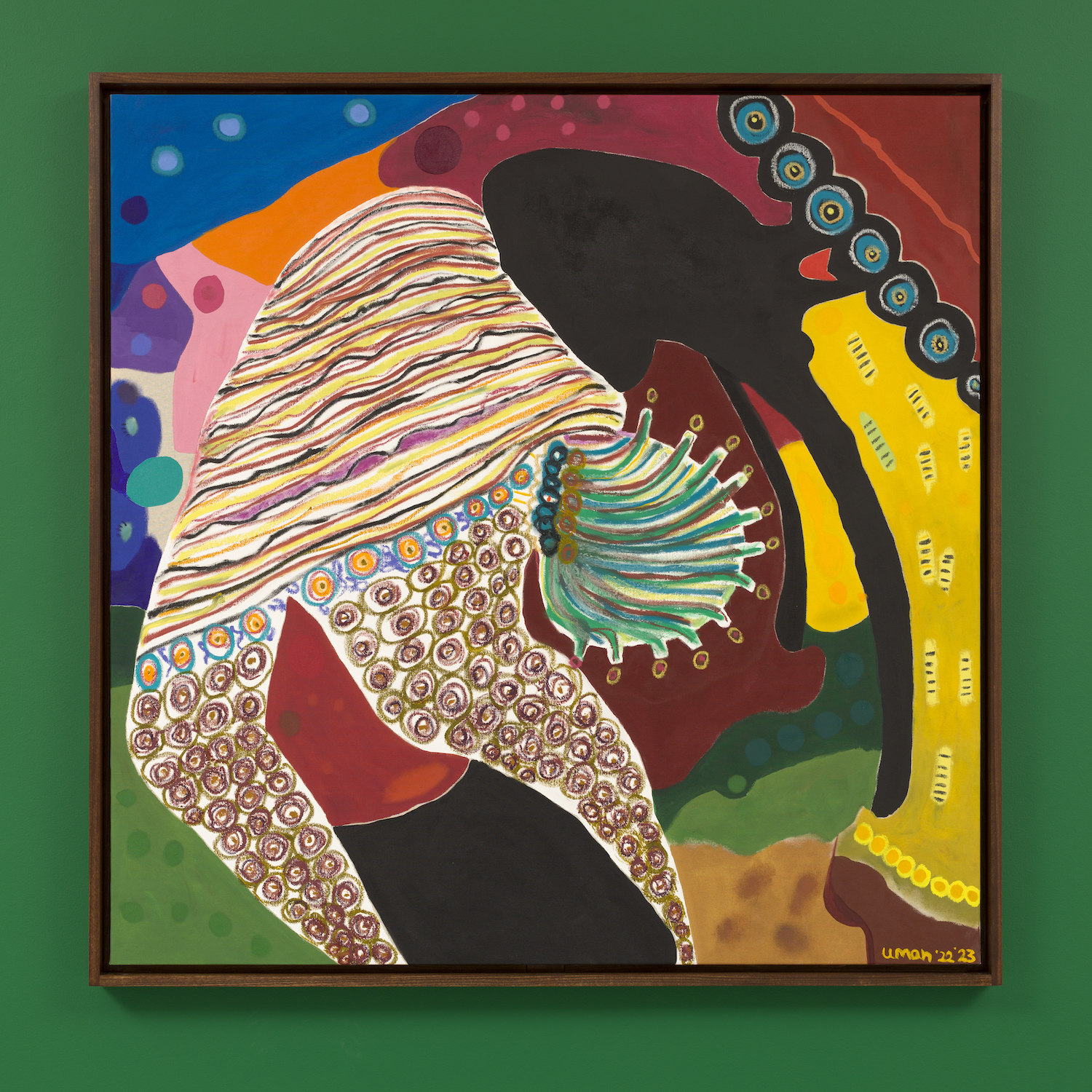

In the meantime, Payot became interested in an artist Vassell represents, the painter Uman. The two dealers decided to give a new arrangement a shot: a full partnership that will be the first in a new initiative for Hauser & Wirth modeled on a framework of collective impact.

Collective impact is a model that became popular in philanthropic circles around 2011. It refers to an intense partnership between organizations (often ones of different scales) to accomplish a shared goal. The criteria for such a relationship are a common agenda, a shared measurement system, mutually reinforcing activities, continuous communication, and a backbone organization. In the case of Hauser and Vassell, they’ll be leaning on transparency and “intensive resource sharing” to develop the partnership.

“It’s an entrepreneurial way of thinking differently in order to develop the career of an artist, on one hand, and, on the other hand, to support a smaller gallery in its development,” Payot said of Hauser and Vassell usage of collective impact.

Vassell started working with the Somali-born, upstate New York-based Uman shortly after opening her gallery, and the works have caught on with collectors. Uman started out selling art on the street in New York in the early 2000s, before a 2015 show at the alternative space White Columns. Downtown New York dealer David Fierman, founder of Fierman gallery, worked with the artist for three years, at Fierman and previously at Louis B. James gallery, and sold her work to both collectors and institutions. Vassell, who began representing Uman in 2022, sold out a booth of the artist’s paintings at the Independent Fair that year, and had a successful solo show with Uman this past spring.

“She is a remarkable artist,” Vassell told ARTnews. “A once-in-a-generation talent. And her work has this capacity for evolution. She needs an outlet to express that that reaches far and wide. But that gives fuel to the capacity to evolve.”

Fiercely protecting such artists from the incursion of larger suitors, Vassell said, is not a good way to further their careers. “When you have a talent like Uman in your stable the reflex might be to build a wall,” she said, “but I’ve been in the business long enough to understand that you can’t challenge a talent that may not stay in place. So you widen the circumference, recognizing the global forces of the market.”

The idea, Vassell said, is to have the best of both worlds: the important context of the smaller gallery, and the support system of the mega. Move to a mega too soon, and a young artist can get lost; stay too long with a smaller gallery and an artist can start to feel suffocated. “It’s the ability to have the sum total of two different, but potent support systems, to create an amplified advantage.”

Artists having more than one dealer representative is, of course, nothing new. When an artist is represented by more than one gallery, things often split along geographical lines: one gallery in Europe, for instance, and another in the U.S. The artist decides which artworks go to which gallery, and for each sale the artist makes a set percentage—50% is standard—and the gallery that sells the work gets 50 percent. (Alternatively, one gallery, the artist’s main representative, can consign work to the another, and take a ten percent profit on the sale.) Under the collective impact arrangement, Hauser & Wirth and Vassell will work as a single team for Uman, sharing their respective networks of collectors and museums, and jointly deciding which artworks go where. The financial split is 50 percent to the artist and 25 percent each to the galleries.

Historically, Hauser & Wirth has taken on numerous artists for worldwide representation, and Payot said that won’t necessarily change. But he sees the non-competitive partnership framework as a step toward mitigating the paradigm where young, modestly sized galleries with rigorous programs, like Vassell’s, risk losing their more successful artists to a larger shop.

“This is not something we will do with every single artist,” he said of the Uman deal. “This is one option among many.”

Such dynamics are hardly new. Around 2016, there was a spate of gallery closures in New York, and many blamed mega-galleries like Hauser & Wirth, Pace, Zwirner and Gagosian for hoovering up artists from younger galleries’ programs, putting them at financial risk. Shortly before the pandemic, certain measures were put into place to help smaller galleries along, like David Zwirner’s suggestion, at a New York Times arts conference in 2018, that the megas help to subsidize their smaller colleagues’ participation in major fairs like Art Basel. Basel implemented the idea just a few months later.

The pandemic may have hit pause on some of these concerns, with art fairs on hold, financial support packages from the government, and the increased ease of selling art online, but recently there has been another round of closures, such as that of Lower East Side favorite JTT, and those concerns about the mega-galleries are back in the spotlight.

Payot says that over the next few months Hauser & Wirth will reveal more of these collective impact relationships. In the meantime, don’t be surprised if you overhear some booth-to-booth conversations between Payot and Vassell at Art Basel Miami next week: both galleries are bringing works by Uman, priced at around $90,000.

The galleries will unveil their first jointly organized exhibition of Uman’s work in January at Hauser & Wirth London.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated Uman was based in Buffalo, New York. She is based in upstate New York.